From Multitudes:

The Unauthorized Memoirs of Sam Smith

As I lay in my bassinet at Washington's Garfield Hospital in the late fall of 1937, I was of course unaware that the world was rushing towards war, that Roosevelt was still struggling with the depression, and that Mado thought I looked like "le petit Jesus."

It was the year that Amelia Earhart disappeared, the Hindenberg exploded, the Japanese bombed Shanghai, the Lincoln Tunnel and the Golden Gate Bridge opened, the average income was $1,788, a new car cost $760, a house $4,100 and a gallon of gas ten cents. If I turned out to be an average American male I could expect to die about halfway through 1997.

I was given my grandfather's name -- all of it. So I became Samuel Frederic Houston Smith. It was more than I needed and my parents further complicated matters by calling me Houston, which left me with two initials on my bow as though I were a steamship of some exotic variety.

Mado was Mademoiselle Julliette de la Morlais, come to guide my entrance into civilized society because the English nanny who had cared for my older brother and sister had gone off for an operation, from which she had almost died.

Mado had come to the rescue once before. My mother, the youngest in her family, had been left to her own devices on my grandfather's estate, but when her parents learned that she had been milking cows and haying, they brought in Mado to introduce some order and class into her upbringing.

Mado was old when we met. I came to think she had always been old, a fact based largely on a photograph of her looking old in a nurse's uniform in World War I, which was a very old war. It was fortunate that I could not speak my thoughts, because I would have asked Mado why she was old and smelled French old and had inexplicable hairs on her chin. It was far better to accept her view that I looked like baby Jesus, a thought that pleasantly colored her attitude towards me.

Part of Mado's role in the cosmos was to cheerfully decorate it. She was always painting something in that delicate French style that helps to give the French a generic reputation for charm. She would paint dishes, cups, moldings, and even -- for me -- a small multi-paneled screen with little happy French people and little happy French flowers. She wanted me to be happy too and when she was around I was. Her impact had been swift and profound. My mother recorded my first spoken phrase: "When asked to come say how-do-you-do to some friends of mine, he ran the other way and said, 'Pas bon lady.'"

A couple of decades later, when she was not only old but very old, she would paint small wooden toy houses and supermarkets and lighthouses that my father was trying to market from his Maine farm as one of a never-ending series of entrepreneurial experiments. The small wooden homes and supermarkets and lighthouses sometimes come out at Christmastime and remind me of the first person I knew loved me.

Lying in my bassinet, I was of course unaware that the typical American baby in the late fall of 1937 was not cared for by its mother's French governess filling in for a recently departed English nanny. Further, among atypical babies who found themselves in similar circumstances, fewer still had a father working in the New Deal and a mother who belonged to the League of Women Shoppers, a group whose recent activities had included boycotting silk stockings in behalf of the organizing efforts of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union and whose subsequent activities would include appearance on the Attorney General's list of certainly, possibly or potentially subversive organizations.

o

Our house, in the middle of historic Georgetown, was new, built on the former site of a trash dump. My parents had considered buying an existing house, but balked at signing the ubiquitous restrictive covenants barring sale not only to blacks and Jews, but to an assortment of ethnic pariahs that included "Syrians and Persians." The trash dump -- next to a row of ramshackle homes with privies outside and impoverished blacks inside -- came without a restrictive covenant.

Georgetown did not appreciate the house my parents built. It was a flat-roofed, boxy, depression-modern structure with brick coated with whitewash that kept flaking off as though possessed by chronic psoriasis. The front door was uncommonly plain except for a little one-way window that I wasn't tall enough to look through. Once the air raid warden -- Gerhard Gessell, later the federal judge who presided over the Iran-Contra cases -- came to our house to chastise my mother for having forgotten to cover the little window in the door with the black cloth that made the rest of our house and all of Washington invisible to the Nazis.

In the stairwell was a large glass brick window that historic Georgetown didn't appreciate either. The dining room had a linoleum floor and the first-floor study was paneled waist-high in sheets of red plywood that would eventually buckle and look ugly and not avant-garde at all.

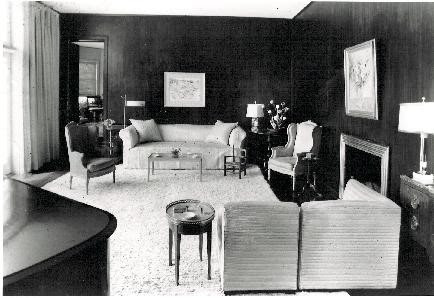

The living room had a wall of glass overlooking a terrace, garden, and the gentle slope of a large backyard where I built massive road systems for my toy trucks, often excavating effluvia from the landfill. I came to believe that all dirt contained bottle shards and sharp pieces of rusted metal.

The wall of glass was constructed of stacked conventional windows and the other three walls were stained burnt umber. There was acoustic tile in the ceiling. The furniture, much of it plush and modern, was largely white except for some antique pieces and a black Steinway grand. The floor was also black. There was a small cement replica of the World's Fair pyramid and sphere on the terrace, and art deco glass and wood objects inside that were heavy and smooth and nice to rub. This house which so angered historic Georgetown pleased me greatly, especially the Capehart record changer in the study that picked up a 78-rpm disc and turned it upside down and played the other side.

|

| THE FAMILY |

Upstairs things became more crowded, but there was light everywhere and pleasant colors and I could ride my trike on the deck above the garage or stand on the roof and look for German planes. The reason it was more crowded on the second floor was because besides my mother and father, Mado, an older brother and sister, and myself there eventually came two younger sisters and, during the war years, two English children evacuated from London. My mother would to the end speak of the latter as "my English children" as though everyone had English children. My mother often spoke with the presumption that everyone had what she had.

One of the English children in fact did become almost a sister and called my parents Uncle Sam and Aunt Eleanor. Older than any of us, Ann returned to live with the family for five years after the war. She was, if you were willing to go as far back as 1812, a cousin.

Ann became the family anthropologist, a participant-observer of acute perception, offering discreet, sardonic analyses of our psyches, motivations and behavior:

"Uncle Sam never wanted girls at all."

He would eventually have four of them. Why not?

"Well, of course, his children were meant to be world leaders and you couldn't be a world leader if you were a girl."

Ann was loved by all and free to excuse herself when the going got tough, although you hoped she wouldn't because things always seemed more pleasant when Ann was around.

It hadn't been easy for Ann to get to Georgetown in July of 1940. She wrote me 60 years later:

I set sail in the Duchess of Atholl in convoy. There was a slight skirmish with a submarine. I remember feeling the ship shudder as depth charges were dropped but we were unscathed and pressed on, though I remember seeing icebergs and wondering.

My mother told me we might well be sunk. If I was dragged underwater, not to struggle. I would come to the surface naturally, then not to strike out to England or America but float on my back, as I had learned at school, until I was picked up.

On August 30, 1940, the Volendam set off with a load of British children for America. It was sunk by the Germans in the Irish sea. All were saved.

On September 17, the City of Benares sailed with many of the Volendam survivors. It was sunk in mid-Atlantic and most of the children perished.

No more British children were sent to America after that.

Ann was dry in wit, resolute in determination, and unflappable in crisis. Decades later we were discussing a recently departed relative who had once been on the periphery of the Bloomsbury Group. What had happened, I asked, to Lucy Norton's ashes? "Well, I suppose they were thrown out with the rubbish." Ann paused and then added, "I think Lucy would rather have liked that."

The other English child who lived with us, a boy, I do remember hardly at all. After the war he never wrote and when my mother eventually found his address decades later, he wrote back that it would be best not to continue the correspondence.

It wasn't until after my mother died, that I found a possible reason why, described on the Gay Social Network:

Among the prominent military personnel accused of sodomy was [the boy's father] Sir Paul Latham, a wealthy Conservative Member of Parliament, who, though exempted from service, joined the army of his own accord. In 1941, he was tried and convicted of "improper behavior" with three gunners and a civilian while serving as an officer in the Royal Artillery. Convicted of ten charges of indecent conduct, he was discharged dishonorably, imprisoned for two years, and forced to resign his seat in Parliament."

And elsewhere this note:

In the Forties, Sir Paul Latham MP was caught writing an indiscreet letter to a man, and tried to kill himself by riding a motorcycle into a tree.

o

At one point there were six small children under ten living in the house we referred to as 3230 for its address on Reservoir Road, although actually it was at the intersection of two alleys -- Scott and Caton Place -- and although actually 3230 had overflowed and some of the small children were billeted in a row house my parents had bought kitty-corner across the alley. Mado had left and Nannie had returned by then and she was in charge of matters in the annex. The two houses were connected by a one-way intercom. Messages and orders could only be sent from 3230 to the annex.

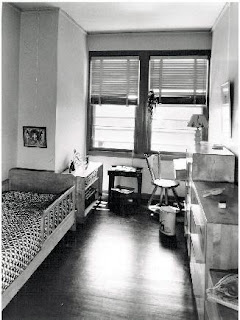

THE AUTHOR'S BEDROOM

I lived at 3230, perhaps because I was meant to be a world leader. My room assignment changed with the flow of siblings and quasi-siblings. At one point I was in a little room in the nursery -- as Nannie's suite of bedroom, child's room and dining/play room was called. My door had a letter slot at an adult's eye-level so Nannie or my mother could look in and make sure everything was all right.

Making sure everything was all right was a preoccupation. There were charts for inoculations and rules about eating and rules about when one had to rest and when one could play and rules about which illnesses (or suspected illnesses) required an enema and which didn't. Young children returning from school were expected to put on their pajamas and rest in bed so that they did not "wear themselves out." And before you went to the dentist you had to brush your teeth with charcoal.

It was serious business; after all, my parents (although no one dared point it out) shared some of the eugenic presumptions of those driving the world towards war. They had, in fact, talked of having 12 children to provide a sufficient Diaspora of their genes. Excessive hospital insistence on bed rest, however, contributed to my mother's contracting phlebitis after the birth of my youngest sister, halting the planned Smith master race halfway along.

My sister Sallie, trained as a social worker, noted that

The procedure for raising children was greatly influenced by BF Skinner’s behaviorist theories. Nannie used to talk of Daddy believing that you raised children just like puppy dogs. Although she bought into a lot of this too, she never forgot the emotional piece

Also I was impressed by her openness to new things. When I would come home from graduate school and discuss new understandings with her, she was always open and interested. She might remark about the difference from her day but she would not claim that they were better. [Our mother], on the other hand, who didn’t really understand all this child rearing stuff either, would respond to whatever I was saying “that’s not the way Nannie did it”. . . and the way Nannie did it was always the last word.

The eugenic assumptions were also common in those days. . . which is probably one reason Hitler got as far as he did before people saw the end implications of those assumptions. Daddy remained caught up in Mendel’s law and what that meant. . .

The nursery dining/playroom had a deck and a map of the world where I would learn to stick pins to mark troop movements in the war of world leaders. The war for me was a matter of maps and toys, and stomping on tin cans, and relatives bringing back American and German insignias for my collection. The only blood I saw was when I climbed on a chair to put some pins in the map, slipped and fell on a pair of scissors, resulting in a permanent scar just above my eye. The war was also parades seen from a government office where my father had worked for a man my older sister called the "eternal general." I loved parades. From that high window the men and the weapons and the vehicles looked like toys and I was sad the day I threw up just as we were leaving for Roosevelt's funeral procession and had to be left at home.

I knew what German planes looked like and I knew that loose lips sank ships. I also knew that because my father had a important government job he had a more permissive gas rationing card than most people. Even so, my father would proudly coast with the engine off much of the way from the Sears on Wisconsin Avenue more than three miles down the hill to Georgetown. Indians had used the avenue in much the same way; they called it the "Rolling Road" and pushed barrels of tobacco down it towards the Georgetown wharves. They didn't win their war.

The worst deprivation I associate with the war was food, and then only after the fact, when the canned cuisine disappeared and I was finally spared the sickening patriotic duty of consuming tinned fruit cocktail downed to imprecations of remembrance of starving Chinese. I felt sorry for the starving Chinese, but I couldn't see why their plight should require nausea on my part.

The food was prepared by Adele, some of it coming from the vegetable wagons pulled by horses that traveled the streets to the accompaniment of their hawkers' cries, some of it coming from Sheehy's market and the best coming in the form of multi-colored ice cream molds of animals and Santas and clowns from Stohlman's ice cream store.

Adelle was the cook. Geneva was the laundress. Emma was the downstairs maid. Leroy was the handyman. And Rosetta was upstairs helping her sister Annie. Rosetta was the youngest, and would stay to the end, outliving everyone and becoming the last person who could still remember how it really was.

The size of my parent's support system did not seem odd; it was all I had known. Besides when we stayed with my grandfather in Philadelphia there were two chauffeurs and a butler with blinding white hair who had fought in the Boer War and never lost his bearing, except when he leaned over to help a small child, which he often did. Stephen would stand nearby during meals, never wincing at my grandfather's repetitive anecdotes nor expressing an opinion about my grandfather's breakfast habit of sitting in a small alcove of the manorial dining hall eating a raw egg drowned in olive oil.

Stephen, like most of my grandfather's staff, was Irish. All my mother's help were black. But I didn't notice that. Nor did I notice that my school and nearly all of Washington were segregated. Nor the difference between our house and the decrepit row of houses next to us, in which our mailman and other blacks lived, nor that their bathrooms were outside while ours were inside. As late as the 1950 census, 226 of Georgetown's 1,663 occupied dwellings lacked a private bath and 135 had no running water. Nor did I find it strange that at Christmas time my mother would visit her poor neighbors with food baskets fully outfitted with hat, gloves, tailored suit, and fur neckpiece.

The blackness and the whiteness of the world were simply there as elsewhere in the south. A friend from Richmond recalls being invited to sing at the church of her family's cook. Her performance was listed on the program as "Jesus Loves Me -- Sung by White Girl." To the end Rosetta would refer to us as her "white children." Things, you were taught, simply were.

My school was several blocks away, a classic red brick

building with small playgrounds on either side. There were four teachers for

120 kids. Two of the teachers were maiden sisters and everyone, student and

parent, called them The Fat Miss Waddy and The Thin Miss Waddy.

Jackson Elementary was a happy school. As far as the thin trail of paper and memory reveal, I was a fine student with a record marred only by a temporary speech defect caused by the inopportune loss of my front baby teeth and problems with my "tables" and spelling. Although the latter deficiency would plague me through life, within a few months the Thin Miss Waddy was writing in her best pedagogical manner to my parents, "I am quite pleased at Houston's effort to overcome his spelling. Our real worth is measured by how we do that which is hard rather than the excellence of the easy tasks."

Miss Waddy lived in a world in which one's real worth was constantly being measured by some nameless judge according to standards as immutable as time itself. Miss Waddy was strict, but she was not cruel or mean. After all, the mystical measurer was sizing her up as well and she was only trying to prevent her charges from coming up short. She may even have had certain reformist inclinations. She let left handers like myself turn our paper sidewise and write down the page rather than forcing us into the contorted position insisted upon by most teachers of the era. We learned about the poor living conditions of Chinese coolies and in one note to my parents she wrote, "I wish that all children could have the splendid books which he has." Miss Waddy's standards did her no harm. She was sighted years later by a fellow Jackson alumnus at the Georgetown Safeway -- in her nineties, still correct and erect.

The official report card of the DC public schools listed a full page of "habits, attitudes and appreciations, which the school considers important." Among them:

o Uses time and materials wisely

o Claims only his share of attention

o Acts promptly at all times

o Appreciates advantages and opportunities offered by school and home

o Learns and applies necessary health rules such as. . .sleeping ten hours with windows open; keeping body clean including teeth and nails...

Jackson almost didn't exist. The city had closed it in an economy move two weeks before the start of the school year. All the furnishings had been removed. But the parents petitioned and managed to reverse the move and classes resumed only two days late. My mother recalled visiting one parent and being told, "I don't see why I think I know more than the Board of Education. If they think this school ought to be closed, I don't see what right I have to say no." My mother's reaction: "And this was just when Hitler was roaring over Europe and you felt this is what makes Hitler. It was terrifying, terrifying."

The older children had started out at private school. But my parents decided they were wasting money with a good public school nearby. The headmistress at the National Cathedral School, which Ann attended, was understanding, but at the boy's school, Beauvoir, the headmistress said, "It's all very well for you to be democratic, Mrs. Smith, but you don't need to go to the gutter." It made my mother furious.

WHAT'S WRONG WITH HIS CADILLAC

My older brother eventually went to Gordon Junior High School. The idea of a public junior high was still new and already it wasn't working well. So the parents were busy there also, organizing patrols to stop knife fights in the halls and rowdiness in the lunchrooms. My brother, four years older than myself, carried a knife and had his nose broken in a neighborhood fight, a fact he managed to conceal from our parents. Gordon and Jackson were all white so nobody blamed the rowdiness or the knife fights on race.

When we left the house, we would travel in my mother's 1936 dark blue Plymouth with a thin red stripe under the windows or in my father's 1938 Cadillac convertible. The latter had four doors, each opening away from its mate. It also had 12 cylinders, soft leather upholstery and two jump seats, but it didn't look as much like a gangster's car as it might have because it was painted a mild green. Convertibles were good to have. Washington was indisputably a southern town. The British considered it a tropical hardship post and let their diplomats wear Bermuda shorts. I considered it very hot and got prickly heat and hated to take naps at Beauvoir summer camp because the canvas cots would rub against the my rash and make it worse. A convertible car was one of the ways you beat the heat. I also came to associate such vehicles with women friends of my parents who owned them -- women who spoke in husky southern voices from smoking too much and had blonde hair and were whatever a small boy thinks of such women before he realizes they are sexy.

My father rarely put the top down on his Cadillac convertible. My mother didn't put the top down either, but she did park her chewing gum on the dashboard because a doctor had told her that chewing gum was all right as long as one chewed old gum.

o

Even with the top up there were the buffaloes at the end of the Que Street Bridge, the fords across Rock Creek Parkway, and the great expanses just outside the city where nothing had happened yet. When I returned to the city later the first thing I would notice would be the sunlight. Washington had wide streets and a law that restricted building heights so the sun could shine on it the way it never could in downtown Philadelphia or New York. I loved the light and the white buildings and the knowledge that important things were happening in the sunshine where good things always seemed to happened.

Washington also had streetcars, noisy double-enders and the streamlined Presidential Conference Cars the heads of the nation' trolley lines had adopted as a new standard the year I was born. Streetcars, Griffith Stadium, and the Library of Congress were about the only places in Washington that were not segregated. In an early successful civil rights protest, Sojourner Truth and other black leaders had successfully petitioned against plans to separate blacks and whites on horse-drawn trolleys.

The segregation of the rest of DC, unlike elsewhere in the south, was one of custom rather than law, but it was just as effective. And when one of the city's streetcars crossed the line into Virginia, blacks were required to move to the rear.

The streetcars stopped traffic as they turned corners, clanged bells and generally displayed admirable supremacy over everything in their way. To me, power in Washington was represented not by politicians or lobbyists but by the streetcars.

Local regulation prohibited overhead wires in the downtown section. This rule, as far as I was concerned, produced two major benefits. Downtown there was a third rail and in snow and ice the streetcars' connectors rubbing against the third rail would produce a gorgeous bluish plume of sparks. Even better, the 30 line ran up Wisconsin Avenue and switched from third rail to overhead lines just a few blocks from my house. There a man sat in a hole in the street. A streetcar would stop over the hole, and the man would raise or lower the trolley and change the third rail connector. To a young boy, observing this border crossing was second only to eating ice cream from Stohlman's.

My parents seemed to like Washington as much as I did. My father worked hard in a succession of government jobs and my mother ran the house and entertained, most notably at a large annual Christmas Eve carol party. She described the ambiance of the city years later:

"It was wonderful. And everyone who was there was interested. Everyone was working terribly hard. Everybody was working for the good of the world."

Washington was much smaller then. It was a time when Mrs. John Nance Garner, ensconced in a rocking chair, served as receptionist for her vice president-husband at his office on Capitol Hill. It was a time when J. Edgar Hoover would write a personal note to my mother regretting that he could not "join you folks for the singing of Christmas Carols on Christmas Eve" because he would be out of town.

Though my father was only a middle level official, my mother would go to the White House with other New Deal wives for tea with Eleanor Roosevelt. My older brother recalls that Mrs. Roosevelt once dropped by our home on the spur of the moment but our mother wasn't home. And my mother remembered sitting at a dinner next to Supreme Court Justice Reed, who approved of her patronage of the public schools because, he said, many of the good students at Harvard were public school boys.

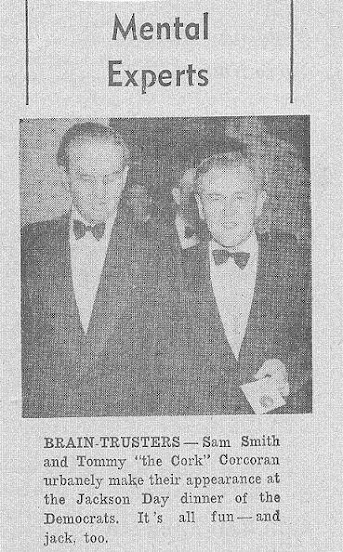

My father had first come to Washington in the last days of Hoover, taking a six month leave of absence from his Philadelphia law firm to work for the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. He returned to Philadelphia, married my mother, and was back with his law firm when Tommy Corcoran, an ex-RFC colleague, called up and urged him to return. My father, Corcoran said, was "missing all the fun."

THE AUTHOR'S FATHER ON A HORSE

My father asked for another leave and was turned down. By the end of the week he had quit and soon left for Washington with my mother. Neither side of the family was happy. My mother's father spoke of Roosevelt as "that man in the White House" and his wife thought that Georgetown was no place for whites to live - unless they had been born there. My father's mother was a leading Republican in Upper Merion Township, and my mother remembered the embarrassment of having to go into the voting hall and being announced as "Eleanor Smith, Democrat" right after her distinguished mother-in-law had been announced, "Gertrude Smith, Republican." On the other hand, this woman had also been chair of the state League of Women Voters and vice chair of Women's Suffrage for Pennsylvania.

My father had gone to the University of Pennsylvania, Oxford University, and then back to Penn for law school, a condition his father had placed on his expedition to England. Over the summers as a student, my father had worked in steel rigging and paint gangs, as a railroad right-of-way inspector and as a surveyor's assistant.

For my mother, politics involved more than loyalty to her husband. She would tell of how she had stayed at the Bellevue Hotel after a glittering ball that lasted until 8 in the morning. At eleven am she was awakened to a strange noise and looked out the window to see hunger marchers on their way to Washington. She said it made her realize that something was wrong with the country.

My father was initially an associate counsel of the National Recovery Administration. When the NRA was declared unconstitutional, he switched to the Securities & Exchange Commission where he ran the investigation of investment trusts that led to the Investment Company Act of 1940. In a 1940s resume he described his work as including "joint supervision over staff of over 30 lawyers, economists, statisticians and analysts for the Securities and Exchange Commission in study and investigation of investment trusts and companies in the United States. This study included holding hearings on 250 companies (many by me), supervision of the preparation of 5000 pages of printed reports and the drafting and carrying forward in Congress of legislation regulating an industry with five billion dollars of assets."

I came across a letter to Tommy Corcoran in 1937 - addressed 'Dear Tommy' and closing with 'As ever' - which my father argued that a minimum wage law would be constitutional. One year later the bill was passed and three years later after that it was upheld by the Supreme Court. In 1940 my father moved to the Justice Department. There he spent most of his time preparing for the fully expected war.

After war broke out, my father, then over 40, went to work for the Foreign Economic Administration in Dakar, buying things West Africa needed and buying from West Africa things the military needed such as fats and oils. Richard Saltonstall in a chapter on my father in Pilgrimages, wrote that he "conducted extremely high-level and sensitive business missions for the government, including the purchase of the fuel oil that got Paton's tanks rolling again across Germany." In a letter of recommendationin 1945, the Army's Adjutant General, James Ulio, said he had purchased $20 million in commodities for the U.S. Army, the equivalent about about $240 million in 2010.

In West Africa he acquired two phobias: bare feet and airplanes. He had learned in Dakar of the dangers of disease from walking around in bare feet. His children were thereafter forbidden to walk inside the house in bare feet, no matter how dissimilar our house was from those in West Africa. His distaste for flying, built up in 100,000 miles of propeller-driven travel during the war, crystallized in a nighttime flight over Africa. The co-pilot came into the cabin and said he understood my father had been to Dakar before and did those lights down there look like it? After the war my father never flew again. My mother was never in a plane.

Nearly a quarter century after my father's death, I was tinkering with an old family desk that I knew had several hidden compartments. A piece of wood suddenly moved and I found myself staring at a small cache of typewritten letters between my parents in the last year of the war.

On March 2, 1945 he wrote my mother from Bern. He describes catching an 8:29 am train to Zurich: "There I talked three hours to the head, or one of the heads, of the Swiss National Bank, named Mr. Hirs and then took the train back here."

Then:

Tuesday I go to Paris probably - if so with the Currie Mission on their train. I come back in a day or two. No gestapo follows me, except possible the Swiss, for they have a wonderful one.

And at the end:

Tell mother that there are plenty of Swiss spies but not German and no female spies. I haven't time for them either.

Then on March 14:

Paris is cold and damp. We left in two 2 1/2 ton six wheel trucks and a jeep with six soldiers, all with guns to protect the load on the way back. . . German tanks and trucks burned up, and turned over off the road, wooden repairs to iron and steel bridges, German prisoners marching off to work, a warning by an MP that two German parachutists had dropped, a railroad locomotive off the bridge and beside the road. . . factories and oil plants destroyed. . .

Lawrence Smith carried a noncombatant certificate which said that if captured he was to be treated as a field grade officer (major to colonel). At his right is his driver carrying a pistol. Smith wrote home: "We had six tommy guns and plenty of ammunition. At one point we were warned two [German] paratroopers had dropped behind the lines."

What my father was doing on this trip from Paris to Bern remains a mystery. About a fortnight earlier he had written to say that he expected to go to Paris in a few days with the Currie Mission on their train. "I come back in a day or two"

Even more startling, though, than the photo of my father on his way to Bern under armed guard following his Paris trip was the following:

Please keep in mind the possibility of coming out here, for it would be wonderful. It depends on the war but then. . .

One month later, with the war still raging, my father, in Switzerland, makes an extraordinary suggestion about which I never heard a word from either one during their lifetimes:

It is my idea that you would rent [a] house for one year, from June 20th say or before, and come here bag and baggage with all of you and Nannie and maybe Mother.

The war would have to be over but it will be in three weeks' time. So you see I am thinking ahead. . . But the important things would be A: that we would be together and B: the children would learn both French and German. . .

Houses in Geneva are cheap and plentiful. Hotels empty, only Berne is full and expensive.

You could embark on a nice boat, after the U-boats are gone, coming to France or England, where I would meet you and bring you through in one day from Paris. There is enough food here, and I will take care of it before you come, because I would not want you all to starve.

Could you and Nannie get to France or England alone? If you went to England, we could take off through France in no time. . .

Your soap and coffee came today. I am a rich man and have loads for months. . I'll be here for five or six month at least, so plan to be with me. . .

Since writing this, I've talked to Mr. Demiene who was with American Express for 21 years and knows the US well and our needs. He thinks it would be very easy to come over and stay here after the German collapse, putting the children in some of the excellent schools , particularly on the French side. You could have a villa with a garden above the Lake of Geneva. . . The gardener would give his services for one half the vegetables and fruit and chickens. .

By June, the idea of bringing his wife, mother and four children to barely post war Europe had simmered down:

Regarding this winter, as I see it there is going to be such a several coal shortage all over Europe. . .that I would not consider asking you to come over with the children. The Vice Consul at Geneva has his ration, someone told me tonight, enough for heating one room. Germany is producing at 3% of her former rate, England and France are way down. Food will be hard, too, but not insuperable. .

The photo of my father and the soldiers continued to puzzle me, especially since it was accompanied by another showing a Swiss moving van backed up to one of the Army trucks. Then in 2009, I was having some art appraised and in the course of a conversation with the appraiser's assistant, who also happened to be a member of an OSS history group. I recounted the story of my father's strange journey and other WWII materials I had found. She said, "It sounds like he might have been part of Operation Safehaven."

She took my materials to an OSS history group meeting and came back with a note from one ot its oldest members: "It appears that Mr. Smith was indeed a member of the Safehaven mission."

My father had never used the phrase, there had never been a hint of any connection with OSS, but the more I investigated, the more it seemed that I had discovered something deliberately hidden all these years.

Operation Safehaven was a secret World War II project aimed at recovering stolen and hoarded Nazi gold, art and other valuables. In the course of my research I came across an OSS summary stating that Safehaven's purpose was "above all, to deny Germany the capacity to start another war." A CIA report below calls this purpose its "overriding goal."

The Safehaven operation was started by the Foreign Economic Administration, for which my father was working. But, while inventing the project, the FEA soon found itself over its head and called on the OSS for help. In classic government tradition the two agencies apparently alternately cooperated and competed. The State and Treasury departments' involvement helped to make it even more complicated.

The Currie Mission, with which my father was involved in some manner, was headed by Laughlin Currie, head of the Foreign Economic Administration. According to one account, "In early 1945, Currie headed a tripartite (U.S., British, and French) mission to Berne to persuade the Swiss to freeze Nazi bank balances and stop further shipments of German supplies through Switzerland to the Italian front."

That was the trip my father had taken. The Currie Mission, according to the National Holocaust Museum, reached an agreement with Switzerland to stop cloaking enemy assets, gold purchases from Germany, assist in the restoration of looted property, and conduct a census of German assets in Switzerland. It adds that Switzerland "reneged on commitments."

Two weeks earlier, my father had "talked three hours to the head, or one of the heads, of the Swiss National Bank, named Mr. Hirs." Mr. Hirs, it turns out, was only the deputy head, of whom David Sanger of the NY Times would write decades later:

When the war ended, the Swiss offered a series of backtracking explanations of their behavior [with Nazi loot] . . When bank records or intelligence reports surfaced, it turned to legalistic defenses, arguing that under the rules of occupation the Nazis had clear title to anything they looted from central banks.

Lengthy negotiations were held in Washington over this prickly subject. A particularly duplicitous deputy head of the Swiss National Bank, Alfred Hirs, blurted out to the Americans, ''Do you want to take 500 million Swiss francs of gold'' -- worth roughly $1.25 billion today -- ''and ruin my bank?'' It was a telling moment, because until his outburst the Swiss had not acknowledged holding anywhere near that much looted gold.

The record of my father's role in all this remains blurred. He was a serious art collector and art was one of the things the Nazi had looted. He had also held a high position in the Justice Department so he was used to keeping his mouth shut.

In fact, according to one news account, Operation Safehaven didn't even become publicly known until the mid nineties, a decade after my father's death.

In 1997, Stuart Eizenstat compiled a report for the CIA's Center for the Study of Intelligence. In it, citing two countries in which my father operated, he wrote;

The overriding goal of Safehaven was to make it impossible for Germany to start another war. Its immediate goals were to force those neutrals trading with Nazi Germany into compliance with the regulations imposed by the Allied economic blockade and to identify the points of clandestine German economic penetration. . .

It is quite clear that Safehaven planners had a good idea of what they wanted to achieve, but it also is apparent that they did not have the slightest idea of how to do it. Although it was evident from the outset that Safehaven would be primarily an intelligence-gathering problem, it does not appear to have occurred to anyone to consult the intelligence services, which were excluded from the planning and implementation of Safehaven until the end of November 1944. Bureaucratic rivalries predominated. Indeed, Safehaven was nearly destroyed by internecine quarrels among the FEA, State, and Treasury, each of which wanted to control the program and to exclude the other two from any participation. . .

The decision was finally taken to invite the formal participation of the OSS. Once the OSS was brought into the Safehaven fold, all the advantages of a centralized intelligence organization were brought to bear. . .

The unique character of Safehaven, which was both an attempt to prevent the postwar German economic penetration of foreign economies and an intelligence-gathering operation, meant that the OSS counterintelligence branch, X-2, also had an important role to play. Safehaven thus emerged as a joint [Strategic Intelligence]/X-2 operation shortly after its inception, especially in the key OSS outposts in Switzerland, Spain, and Portugal, with X-2 not infrequently playing the dominant role. . .

In Nazi Europe, neutral Switzerland carried out business as usual, providing the international banking channels that facilitated the transfer of gold, currencies, and commodities between nations. Always heavily dependent on Swiss cooperation to pay for imports, the Reich became even more so as the ultimate defeat of the National Socialist regime became obvious and neutrals grew more wary of cooperating with the Axis belligerents. . .

In this critical situation, the Swiss banks acted as clearinghouses whereby German gold--much of which was looted from occupied countries--could be converted to a more suitable medium of exchange. An intercepted Swiss diplomatic cable shows how, allegedly without inquiring as to its origin, the Swiss National Bank helped the German Reichsbank convert some $15 million in (probably) looted Dutch gold into liquid assets. . .

Fortuitously, the restoration of access to Switzerland through France in November 1944 made it possible for the first X-2 operative in Switzerland to enter the country by the end of the year. By January 1945, X-2 was up and running in Switzerland, and by April it was able to provide OSS Washington with an extensive summary of Nazi gold and currency transfers arranged via Switzerland through most of the war. . .

Despite its liberal democratic traditions, Sweden was Nazi Germany's largest trading partner during the war and almost the sole source of high-grade iron ore and precision ball bearings for the German war machine. . .

Another CIA report states:

Within the OSS, Safehaven fell largely under the aegis of the Secret Intelligence Branch, responsible for the gathering of intelligence from clandestine sources inside neutral and German-occupied Europe. But the unique character of Safehaven, which was both an attempt to prevent the postwar German economic penetration of foreign economies and an intelligence-gathering operation, meant that the OSS counterintelligence branch, X-2, also had an important role to play.

What my father's precise role in all of this, I'll never know, but if I hadn't stumbled upon that hidden compartment in my parents' desk, I would have had no idea that he had been somehow part of the one of a major secret operation designed in part, amazingly, to prevent the Nazis from ever starting another war.

History had taken a turn at home as well:

MY MOTHER, APRIL 14, 1945 - I think that I last wrote you on Thursday, when we were still quite stunned with the news, which came suddenly in the midst of a quiz broadcast: "The President is dead." Then, little by little, the details came, with all radio programs cancelled and only lovely music . . .Mrs. Roosevelt was marvelous, as one would expect. She was opening a thrift shop at the Sulgrave [Club] when the White House called asking to come back at once for an emergency. . . Truman immediately went to the White House, and when he asked Mrs. Roosevelt what he could do for her, she replied by asking what she could do for him. . . It was all so tragic, Sam, Anna at the hospital with a desperately ill child, and the four sons at war, Franklin getting the message on the bridge of a destroyer during a battle. . .

Friday morning I had planned to paint the nursery, which was lucky as I was able to listen all the time to the radio. In fact I started out at 6 am and to hear Arthur Godfrey was my complete finish. Again and again, that is the thing that impresses you. The personal feeling that everyone has. A sailor in the Pacific, saying "It's just like losing a member of your family." . . .

Sam, does all this sound awfully sentimental and queer from afar? I can promise you that it wasn't that way. It's been the most genuine thing I have ever felt, not only in myself, but with everyone. . .

Sunday afternoon, downstairs by the fire, as it is cold and damp. I have just woken up from a deep and exhausted sleep, after a morning of church here at home conducted by Houston [I was then seven] with hymns, the Lord's Prayer, a psalm and a Bible story read by him. It was very cute and well entered into by the others. .

And what will the future hold for us? I for one hope that you won't be too long in coming back. Your young need you. Even with you here we are underhoused and undermanned for five big children. I wish I knew what I did wrong. . . but certainly it's not right that I must yell at them the way I do. I do feel that a lot of it is because they are cooped up and so overflow in body and spirit the bounds of the house. Lewis broke the window in the hall by playing ball in the house with Meredith yesterday, and I must confess that all the pent up feelings of the last three days burst forth on the child. He is going to pay for it and attend to the ordering of a new one.

Houston gets quite tired from camp, I think, and then I do find it difficult to get his [very curly] hair cut as often as I should and so I think he gets teased which doesn't help his morale. I feel that I do so much that I don't do any of it well. . .

MY FATHER, APRIL 14, 1945 - I am distressed about the President. He certainly influenced our lives. I am not sure he will not be greater in death than in life. Tragic he had to go but maybe best for him. We have to get on without him some day, and it may not be too soon to find out. I am glad he died the great man that he was.

MY FATHER, AUGUST 11, 1945 - What a day with the possible end of the war. We closed down at 5:30 and gave the office crowd a party. It is a funny feeling that it may be all over, and I don't know what I shall do with myself when I get home and no war. . .This Army man came from Paris raising the devil about watch deliveries falling behind and so my day has been completely gone.

MY FATHER, AUGUST 12, 1945 - I wrote you a hasty note yesterday, for I was in a bit of a stew. One of our people had sent back a report showing that only 30% of the watches ordered had been delivered, whereas 99% had been delivered. He counted 95,000 as undelivered in Paris ones that weren't due here until July 30th. And 35,000 which had been delivered to the inspection company. General Allen and others in Paris were upset and sent a troubleshooter down yesterday. He was tough and thought we were trying to cover up. I was tough, too, and we got it straightened out satisfactorily, but it has ruined my weekend.

o

My father's physical and verbal anger was just there and the strongest word I had for it was "strict." Both my parents believed that toughness "builds character" and would not hesitate to "lay down the law" or, for that matter, the hand on the backside. Many decades later, I would read about parents going to jail for laying down the law in such a fashion.

Spanking and whipping, though, had the advantage of brevity. The lectures, the interrogations, the derogatory character assessments could seem as interminable as they were disparaging. My father was a man of Vesuvian temper, mitigated primarily by the fact that there were eventually six of us. Since he couldn't be angry with all of us at the same time, life became a game of musical doghouse in which one survived a round only at someone else's expense. Even Rosetta and Nannie, brilliant as they were at circumventing the land mines concealed in the social intercourse of our house, were occasionally targets. I soon discovered the virtue of simply absenting oneself from potential scenes of conflict. My mother would later occasionally claim that, "it never occurred to me that my children would not turn out well," but it was a claim belied by my parents' fury when we strayed from righteousness.

My parents believed that your children were an extension of oneself -- a reflection of one's character, taste, intelligence, and status. Our job was to fit into the larger scheme of life they envisioned for themselves. When we failed there was anger.

Nannie also kept a strap handy, but it was used not to correct character flaws but genuine, indisputable misbehavior on the part of the very young. Once one graduated from the nursery, she seldom expressed more disapprobation than a weary disappointment when you had failed to live up to her standards. Even that was rare, for it was to Nannie and Rosetta one went to for support and praise and these commodities were too precious to risk their loss.

My mother would check with Nannie each morning to see how things were going. My father's curiosity was more limited. Rosetta remembered my father being accosted by Nannie who asked him, "When was the last time you saw your baby, Mr. Smith?" He paused, explained that he was in a hurry, and continued downstairs.

Rosetta rarely spoke of her own father -- "he traveled a lot" -- but of mine she once told a friend, "he treats those children like a colored man." I suspect she was thinking of both our fathers when she said that.

HILDA PRITLOVE, BETTER KNOWN AS NANNIENannie, like my parents, had perfected the presumption of authority. It was an act, but for a young child convincing enough. Nannie was, in fact, Miss Hilda Pritlove. She had lived a full life long before she came to work for my parents, including a stint with a disturbed lady who once locked her in a steamer trunk, and another with a husband and wife who leased a 100-room house and left Nannie and their small child in it with only the servants. Each night Nannie would eat alone in a huge manorial dining hall as a butler waited nearby and a footman stood behind her chair.

On another occasion, Nannie worked for a couple who lived in the Plaza in New York City and kept their two pet penguins cool by constantly refilling a tub with ice. Every afternoon the penguins would be put on a leash and walked by the chauffeur.

And Nannie took care of the family of the man in charge of Pan AM in Europe. they had rented all 130 rooms of Lord and Lady Besborough's Panshanger. Among the people she met there was the famed art dealer, Joseph Duveen. According to my sister Eleanor:

Mr. Rogers said that Duveen was coming, that he could not be there but could Nannie follow him around and stop him from stealing any paintings. Nannie took Duveen around for an hour when they finally reached Lady Besborough's boudoir. Suddenly Duveen grabbed a Canaletto off the wall and started to roll it up, saying he had been looking for that painting . Nannie rang for the footman , who tackled Duveen , rescued the painting and shot Duveen out the door.

Nannie also had a tour with the grandchildren of Alexander Graham Bell. One day the phone stopped working. Bell, who preferred to work at night, instructed Nannie to wake him when the repairman came. The service call was not going well when Bell walked into the room in a nightgown and turban and said, "Let me have a look." As Bell knelt on the floor, the repairman turned to Nannie and said, "What does that old goat know about telephones?"

Nannie believed in moderation and regular habits, which in her view -- to the end of her nine decades, more than five of them spent with our family -- included extensive walking and close to a half-pint of whiskey every night. She could be extremely pragmatic; one of her favorite sayings was "The truth must always be spoken, but the truth need not always be told." And she believed in cod liver oil and enemas and prescribed excruciatingly long bed rests after the mildest cold or sick stomach.

Unlike my mother, however, she did not regard illness as a character flaw. When you sneezed in front of my mother, she would say, "Ah-ha!" as though discovering a misdeed. Illness always had a cause rooted in negligence or misbehavior.

Nannie, on the other hand, was imbued with a can-do English spirit, which was of inestimable aid to children whose parents often presented only the gloomiest prognostication of the future based on their burgeoning character deficiencies. Nannie would tell of the time early in her life when a doctor informed her she only had six months more of life. "In that case, " she announced from her hospital bed, "I'm going home." She did and lived another half century.

THE AUTHOR DURING THIS PERIOD

My father had been strongly influenced by his years at Oxford where he had socialized with Britain's upper crust. The Oxford studies were a trade-off with his father, of whom my father rarely spoke. My grandfather had agreed to finance Oxford and in return my father had agreed to go to law school.

There were intimations of profligacy and high living during that period, including a story that he had once skied naked with the Oxford team in Switzerland, but by the time I came along such tales, in both fact and reminiscence, were strongly in check. I did know that in some University of Pennsylvania student journal there was a reference to him as "Sapphire Sam" with "sapphire studs on his underduds."

Growing up, I learned from family papers, my father clearly had something more in mind than quiet pride in a rooted community where his family had lived for over 200 years. My father, in fact, was an early front runner in the student magazine's contest for Penn's most "pulchritudinous man." Reported the school paper: "'Smiling' Sam, they call him, because he owns a face and figure like the hero in a starched collar ad - hair as blond as your favorite manicurist's - crisp curly socks."

'He's a beaut,' to use the words of the camps and 'twill take a smart-looking chap to outlook him as the 'handsome champion' when the final award is made at the end of the year.

He had also been a leading football player for Haverford School, a member of the gymnastics team and the class prophet. And in college he had been an editor of the Pennsylvanian, undergraduate chairman of the Mask & Wig theatrical group, and chairman of the Ivy Ball.

Long after my father died, one of my sisters uncovered correspondence from a friend that evoked a man I never knew:

Sammie, Old Kid, you're a brick (that's a B, not a P) to write to an old sailor and plumber! Glad you appreciate my efforts to be a good correspondent . . . But let me tell you one thing, young fellow. There's a girl here who has CFB's misty girl beat for a goal. She's the most popular girl up here and she surely does deserve it. She won a dancing competition last night and is the most wonderful dancer that ever ate hash on Thursday. Everybody in NEH [Northeast Harbor] is giving this girl a rush and so am I. Her name is I. Virginia Hecksher. Do you know her? She said to send you her love and to tell you to write, for gosh sakes. There has been a dance ever night for a week or more and there isn't any let up yet. It's worse than Phila. in the Xmas Holidays.

My father, like my mother, considered children as one more important task that a person of importance undertook, but not too personally. My father used to joke about the horse he owned from which he had once fallen in Rock Creek Park and had hailed a taxicab to chase and recapture. The horse had become too expensive and he said he eventually had to decide whether to keep his horse or his latest child. He would tell the story in front of the child and everyone would laugh.

Once I mentioned to Rosetta my mother's unwillingness to have our young son stay with her for awhile. "I've raised one family," my mother had said, "and I'm not going to raise another." Rosetta, who virtually never offered a political opinion, looked up sharply and said, "What does she mean she raised you?" On another occasion she added, "They never paid you no mind."

Rosetta, as usual, was right. We had been raised in the British upper class manner, according to which servants and schools were expected to tend to the details of child-rearing while the parents handled major policy.

Thus it was that dinner at our house bore remarkable similarities to a college seminar. When he was home, my father presided and directed the conversation, or sometimes interrogation, concentrating on matters that interested him or that he considered important for his children to know or think about.

These included family history and world affairs and, on occasions, a formal moot court during which siblings would be expected to argue opposing sides of a major issue. On Sundays in Washington, there was also poetry. We were expected to have memorized all or part of a poem. If you didn't get it right one Sunday, you did it again the next, and the next, until the lines seared the brain like burger on a grill. The marks are still there, although fainter.

I don't recall minding the task that much. After all, in the poetry was a romance that helped to mitigate the unromantic reality of Sunday dinner. And I thanked whatever gods may be for my adequate memory.

Besides, for several years during the war my father was overseas. Thus critical months of boyish mischief went without the rigors and pain of his guidance. Things were less cosmic with my mother in charge. She listened to Arthur Godfrey in the morning and laughed at the Great Gildersleeve in the evening. My father considered such programs a waste of time.

Outside our house, I remember being truly afraid only once in Washington. I was at Mr. Butt's camp near what is now Sak's Fifth Avenue. I was astride what seemed an enormous horse that -- together with the other horses nearby -- suddenly started rearing and bucking. I stayed on and might have forgotten it but for what happened shortly thereafter. During a trail ride I began lagging behind. The counselor made me dismount and hold my horse while the rest of group rode out of sight. I stood in unmitigated terror with the perfectly placid horse until the group returned, seemingly days later.

That was the worst I can remember of the Washington beyond my own house. A few minutes in my first ten years. It was hard not to love a place as kind as that.

Then we moved to Philadelphia.

No comments:

Post a Comment